Before Christmas, there was the gathering.

Not the polite, scheduled, two-hour affair we recognise now — but something louder, looser, and far more consequential. A winter gathering that bent rules, softened hierarchies, and briefly suspended the ordinary order of things.

This was not Christianity in rehearsal. These traditions were already ancient by the time the Church arrived.

Across Ireland and much of Europe, pre-Christian societies marked the final stretch of the year not with quiet reverence but with noise and excess: food and drink, storytelling and song, generosity and confrontation. Late December was not holy. It was human — riotous, communal, occasionally violent. In modern terms, it was a collective refusal to bow quietly to fear: fear of hunger, of cold, of scarcity, of what the long winter might yet demand.

The Celtic year did not tick by on calendars. It turned on labour, livestock, and land. Its markers were practical: animals brought in from the fields, slaughter completed, stores tested for the first time under real pressure. By late December, winter had declared itself fully. You now knew whether what you had laid by would carry you through — or whether the months ahead would be lean and unforgiving.

If you had enough, you gathered. If you had more than enough, you shared. And if you had power, this was the moment to display it.

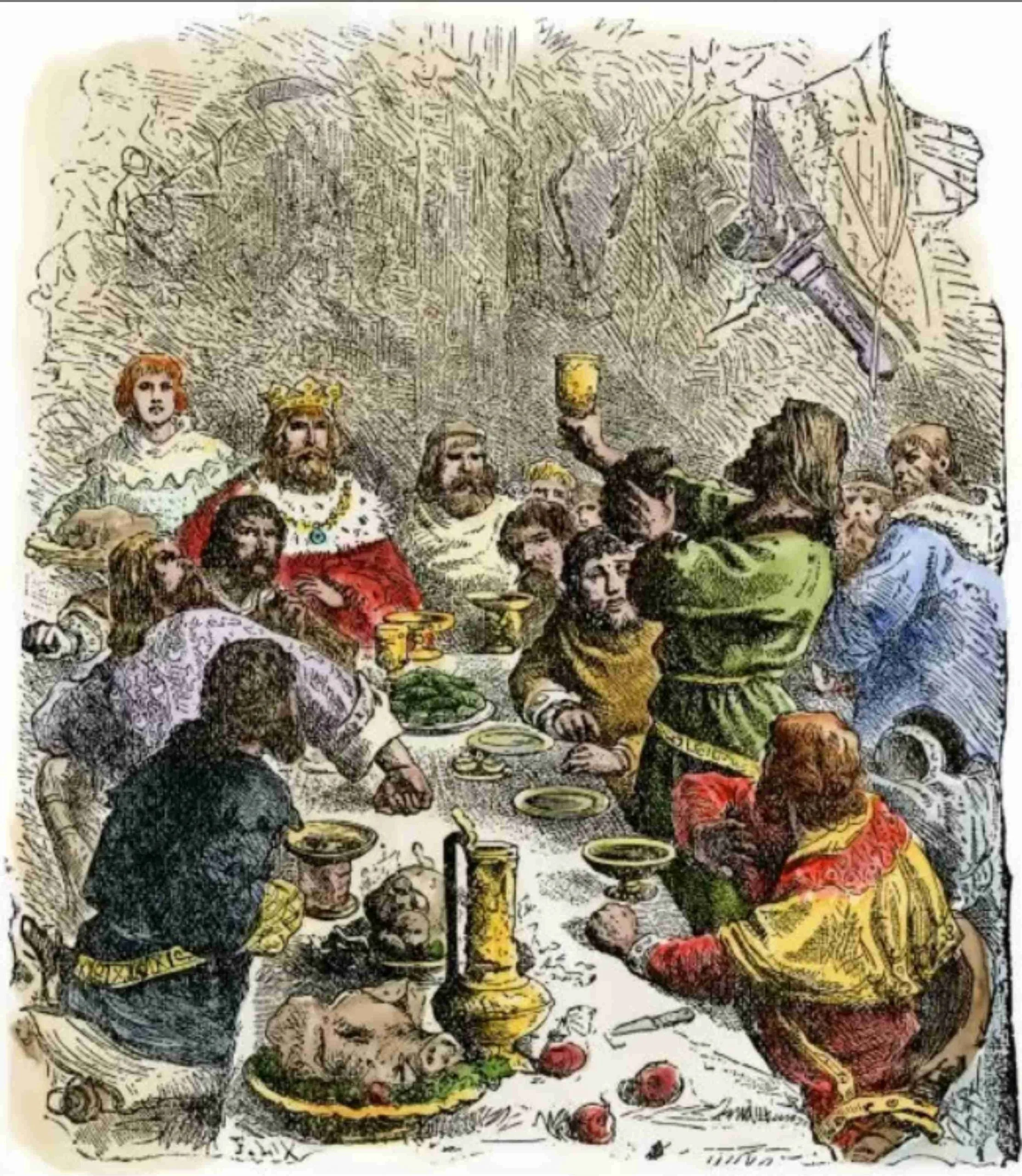

What these winter feasts really were

These were not gentle celebrations of returning light. They were pragmatic, political, and deeply social affairs. Feasting was both generosity and performance. Elites demonstrated benevolence — and sometimes dominance — by feeding others. There was urgency to it, even desperation: a need to consume what would not last, to turn perishable abundance into shared memory.

Animals were slaughtered because they could not be fed through late winter.

Fresh meat was eaten before it spoiled.

Ale and mead were brewed for this narrow window.

Debts were settled. Alliances affirmed. Disputes aired — sometimes peaceably, sometimes not.

Hospitality laws mattered. To refuse food or shelter in winter was a moral failing of the highest order. Those with abundance were expected to give to those without, not as charity but as duty.

Winter feasting reminded people of a hard truth: no one survived alone. Hierarchies loosened. Voices normally unheard were allowed space. Travellers, outsiders, and the poor were fed because exclusion in winter was not just cruel — it was dangerous, practically and spiritually.

The merry part (and yes, it was real)

Merriment did not mean novelty jumpers or background music. It meant loud rooms and louder conversations. Singing that was enthusiastic rather than accomplished. Long stories, told again and again, because repetition itself was comforting. Eating and drinking that blurred the edges of status and restraint.

There is strong evidence of ritualised misrule: mockery of leaders, role reversal, deliberate disorder. These gatherings acted as a pressure valve for societies that were otherwise rigid and hierarchical. December was allowed to be messy. Order would return in spring.

When the Church arrived

Christianity did not invent Christmas cheer. It redirected it.

The Church was adept at this — at recognising what people already valued and giving it a new frame. It did not erase the winter gathering. It reinterpreted it.

Consider Samhain becoming Halloween. Easter aligning with the vernal turning of the year. Christmas settling into the deep of winter. The Church looked at existing rhythms — feasting, gathering, generosity — and retrofitted them with Christian meaning.

The timing stayed.

The feasting stayed.

The emphasis on generosity and peace stayed.

Only the story changed.

This was not accidental. Suppressing midwinter celebration would have failed. Instead, it was absorbed, baptised, and reframed. Christmas did not replace the winter feast or the solstice; it pulled up a chair at the same table. Over time, the old meanings faded, replaced by new ones — sacred rather than seasonal, theological rather than practical.

The darker edge

It would be dishonest to pretend these gatherings were all warmth and goodwill. They carried a shadow. Winter feasts often marked the beginning of real scarcity. You ate well because you did not know what January and February would bring. The celebration had defiance in it: eat, drink, sing now, because silence and hunger might follow.

And there was exclusion. Hospitality was expected, but not universal. Those outside the social web — criminals, the ostracised, the rule-breakers — were often shut out. Feasting highlighted both belonging and absence. Who sat at the fire mattered.

What remains

Strip Christmas back far enough and what remains is not doctrine. It is instinct.

People gather when it is dark.

They eat well when they can.

They open doors wider than usual.

They allow noise, laughter, and loosened rules — briefly — because endurance requires relief.

Before Christmas, there was feasting and gathering. They were not about holiness or redemption. They were about getting through winter together: with full bellies, shared stories, and enough warmth — physical and human — to reach another spring.

In that sense, at least, the spirit we celebrate now is far older than the holiday itself.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Happy Christmas.